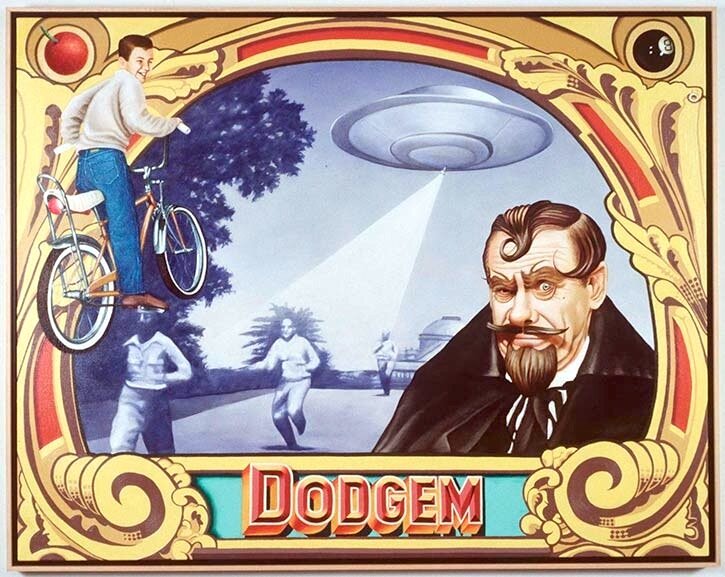

During my shifts as a Museum Experience Representative at the Triton Museum of Art, I spend the majority of my time in the rotunda welcoming patrons into the museum. From my vantage point at the front desk I can clearly see three works by Bay Area artist William Maul, “Charter Members of the Deadbeat Club,” “Man’s First Flight to Venus--The Female Planet” and “Dodgem.” These playful works are part of Pop. Funk, and Just Plain Fun! an exhibit featuring Pop and Funk art by Bay Area artists from the museum’s collection. The collection of paintings displayed are bright and bold, blending each artist's unique style with well-known pop-culture references.

One day as I sat at the front desk listening to the low mumble of voices in the galleries mix with the excited chattering of birds outside, a man and woman entered the museum. The pair did one lap of the rotunda before the man returned to my desk. He leaned in slightly and said. “I painted those,” gesturing to “Dodgem” and his other works.

“Oh! You’re William Maul?” I said, surprised and delighted.

“You can call me Bill!”

“Is it strange to see these paintings again after so long?” I ask.

He smiles with his eyes and nods. “A man bought these paintings from a show. I had no idea the Triton owned them until recently,” he explains.

He pauses, shifting his weight back on one leg and tilting his head. I often do this too when looking at paintings of my own, shifting my perspective ever so slightly to understand the composition from all angles. A professor of mine once told me that if you pay attention, you can always pick the artists out from a museum crowd because they “dance with the work,” moving as close as they can, then back, and finally side to side in an effort to understand the way it was made. Bill Maul was dancing with his paintings. “This is actually my favorite painting on display,” he says, gesturing to “Dodgem.” He looks at it like an old friend. The dance continues. “Would you like to hear about it? It’s a bit dark though.”

I assure him I would.

“That’s me,” he says, pointing to the teenager on the bicycle. I look between him and the boy, noticing now the resemblance hidden by age. Although he didn’t realize it at the time, his uncle bought that bike for him as a distraction. His mother struggled with severe mental illness for years, checking in and out of institutions before taking her own life seven years later. He narrates the painful details of his story to me in a matter-of-fact tone like a professor giving a lecture about the facts of another person’s life. Each of the elements in the painting symbolize a part of his experience of his mother’s illness. The grayscale scene of terror and chaos pulled from the 1956 science fiction classic Earth vs The Flying Saucers speaks both to the sense of uncertainty and chaos he felt, but also to the soothing glow of the black and white TV sets of his childhood. For Bill, pop culture, and TV specifically served as an escape from his own reality. The artist gestures to the man in the cape. “Do you know who this is?” He asks. He isn’t at all surprised that I do not. I learn that this cartoonish villain who I would often spot out of the corner of my eye is Sir Graves Ghastly, a TV personality popular during the 1970s. As a child, Bill idolized the character and even sent a letter to him asking for his autograph. He laughs when he tells me that he received only a grainy xerox of a signed photograph in return. When TV wasn’t enough to distract him, Bill would go to the carnival--a place which has historically marketed itself as an escape from the mundanity of regular life--to ride the Dodgem bumper cars; hence the namesake of the piece.

After he finishes talking about the painting he grows quiet and still. “It’s all about escaping,” he says finally.

Although he doesn’t elaborate further I can see why this painting is his favorite of the group. It is a painting as much about his mother’s illness and his coping mechanisms as it is about the origins of his voice as an artist. What began as a way to cope with familial trauma and tragedy has turned into a lifelong artistic obsession. To look at Bill Maul’s work, with all its humor and contradiction, is to witness a celebration of the pop culture that saved him.